10 Questions for A Creative: Tim Whitten

Tim at work weaving a bellrope

Words by Kyra Shapurji

Tim Whitten, lives and works in Deer Isle, Maine where his shop, Marlinespike Chandlery, houses found nautical curiosities and his intricate, timeless rope work that ranges from beckets, ditty bags, and bell ropes, to name a few. He has partnered with Levi’s, the clothing and denim brand in the past, and he was recently awarded a fellowship from the Maine Arts Commission.

Find out more about Tims work on his website.

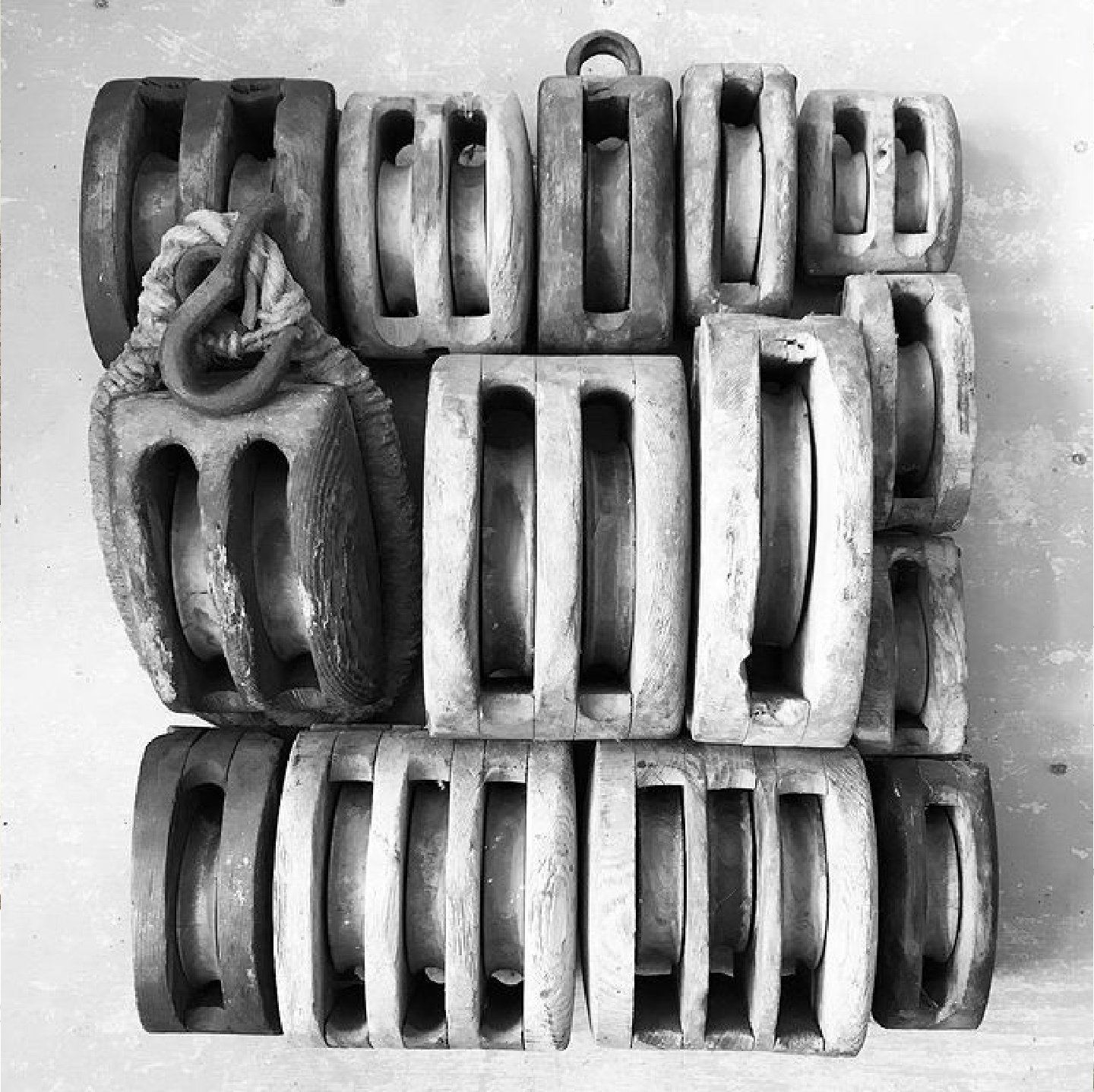

Examples of marlinespike work. Various woven bellrope designs.

“I believe that the further one pursues engineering and science, the more of an art form it becomes. Scientists have to think creatively and philosophically to perceive problems that exist and then think even more creatively to formulate a solution. The best solutions are often referred to as elegant in nature. I think this mode of thinking describes how artists generally approach their work as well – in other words, skilled artists are taking a scientific approach. ”

Marlinspike Chandlery Shop windows overlooking Stonington Harbor.

KS: Let's talk about your shop name--Marlinespike Chandlery--it is after all, how I came to find you and your spot in Deer Isle, Maine while vacationing. I was intrigued and enticed to see what was behind the door of this original shop name. What is its genesis? What were you thinking about when creating the shop and the story you wanted to tell with your craftwork, artistry, and gathering of sea objects for the home?

TW: I opened my store in 2008, and I recall thinking for a long time about what to name the shop. I had published my website in 2002 and naming that was relatively easy because the genre of my work is known as ‘marlinespike work.’ A marlinspike is a conical steel tool used by sailmakers and riggers for splicing and working with cordage.

If you pick up a tutorial book on sailing, invariably there will be a section entitled ‘marlinespike seamanship,’ which typically covers basic knots and splices but also sometimes an introduction to the more ornamental aspects such as woven mats and lanyards. The only complicating factor in naming my website was the modern, more common spelling of the word was already being used as a domain name, so I had to revert to the more traditional spelling of the word "marlinespike" which included the "E" in the middle.

Somehow the word ‘chandlery’ was in my lexicon, but I recalled from my youth, stores such as the hardware store in Eastport, ME that claims to being the nation's oldest chandlery, and it was also a memorable name that stuck with me from visits to Mystic Seaport, so it had a very quaint connotation. I didn't know the meaning to be anything other than a sort of general store but with a maritime focus. So it made sense, I would name the shop the ‘Marlinespike Chandlery,’ which I translate to the store for fancy woven rope work.

Marlinespike Chandlery storefront in Stonington, ME

KS: Taking some further steps back, what led you to Maine and specifically the setting of Deer Isle? It's a special area of Maine and the U.S. that has managed to still keep a low profile.

TW: My parents were from Maine and my grandparents on my mother's side were originally from New Brunswick, Canada, and so when I was young, a lot of time was spent Downeast and in the Maritimes. I've always loved the smell, rain and fog of the coast.

I had met my wife who is a school teacher and we were looking to relocate from Potsdam, NY, and it turned out we had mutual friends living here on Deer Isle that we had visited, and that was the first time I'd visited the island. We bought a tiny fixer-upper, and I anticipated just running my online business and working on the house. It was only after making the move in the spring of 2008, and finding the space for rent totally by chance that later that summer I became a shopkeeper. There is no doubt that finding myself there, in a dedicated work space, led to an awakening in my work.

Whitten's workspace in the back corner of the Marlinespike Chandlery.

KS: How do you see the Maine coast and its landscape infusing itself into your work and shop?

TW: In addition the traditional forms of marlinespike work that I had been making, I began to see other ways of employing the fiber techniques in combination with other materials such as stones and shells, but I also recognized that as small as my rented shop space was, I would have a hard time filling it with my own work, so I began to more actively collect and acquire objects of interest, and my shop began to evolve into a eclectic mix of not only my own work but other art and antiques, and anything that I found interesting. It's very satisfying to me when people come in and slowly try to take everything in and remark on how "curated" the space feels. I see it now in what I've created but a curated collection was never my intent. it just happened that way kind of by chance.

Some items hanging around in the Chandlery.

KS: I've read you studied and went to school to become an engineer, and not art as most people would probably assume given this line of work. How do you see engineering playing a role in this rope work, and how do the two merge today in your life?

TW: I believe that the further one pursues engineering and science, the more of an art form it becomes. Scientists have to think creatively and philosophically to perceive problems that exist and then think even more creatively to formulate a solution. The best solutions are often referred to as elegant in nature. I think this mode of thinking describes how artists generally approach their work as well–in other words, skilled artists are taking a scientific approach.

I think being educated as an engineer served me well in preparation to pursue the line of work I've found myself in, but obviously, this isn't what I thought I'd be doing when I started college as a freshman. The twists and turns of life and fate opened doors that I could have never anticipated or planned for.

When my artistic path began, I had recently completed my dissertation in the field of mechanical engineering, and it started simply as a hobby, but I put the website together, and before I knew it, I was sending out more of my rope work pieces than engineering résumés.

Woven handles made by Whitten. Examples of intricate marlinespike work, typical of the handles (known as beckets) used on traditional sea chests.

Antique sailmakers and rigging tools. Fids, prickers, serving mallet and serving boards.

KS: Your ‘artistic path,’ can you share the journey and how you arrived to create your rope work, marlinspike seamanship and this specific creative art form?

TW: I recall rereading Moby Dick at the time but coincidentally a book on fancy marlinespike work had reappeared on a bookshelf in my parents’ house. It's a book that was originally presented to me as a gift from my Dad when I was younger and involved in scouting.

I was able to extract some useful things from it at that early age, but some of the more complicated aspects were beyond my adolescent self. But opening the book years later, and with three engineering degrees, seemed to have made all the difference, and I could clearly see and visualize the material in the elaborate line drawings. Plus with the aid of the internet, I was able to source the traditional and appropriate materials in a way that would have been next to impossible for me in the mid-1980s. Had Youtube existed I probably would have made use of instruction found there, but I am solely self-taught from material learned from printed books. It's worth noting however that much of that print material is presented in the absence of hands, and the work is basically all handwork, so I have developed a lot of techniques on my own.

Becket details.

“As my library grew, I acquired books detailing early rigging practices, and I realize now that my interest was in the geometry and structure of the rigging and rope work, not so much the dynamics of the rig but the artistic aesthetic of the work. What impresses me now about the work in general, and why I think I was drawn to it initially is the richness in the pattern, texture, and geometry of the work–lines, squares, diamonds, and spirals.”

Shop corner in the Marlinespike Chandlery. Whitten also collects various objects and maritime antiques.

KS: I'd love to hear specifics on your weaving and designs, and where you look for inspiration when you're creating these very functional handles / sculptural fibre art.

TW: The aesthetic that I try to maintain with bellropes, beckets and ditty bags is that of the works made during the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. I'm not trying to recreate period-correct reproductions but the use of natural fibre is important to preserve the general look. I use a lot of cotton because it is readily available, but I also like using hemp and linen. I don't use a lot of colours so the palette is mostly limited to whites and browns. When I do add colour, it tends to be a uniform treatment either in the form of staining or dyeing the entire piece.

Last year I received a fellowship from the Maine Arts Commission and the feedback I heard about one of the main criteria for why I was chosen was the smooth transitions I can create from one marlinespike technique to another. I was very pleased to hear that because it’s one of the main factors that I consider when making a piece. That is, I feel that the transitions are important in order to create a finished piece with an overall sculptural coherence. And that aspect of my work is what I think is most distinguishable about my bellropes and beckets.

Sea chest becket details.

Moser sea chest featuring becket handles made at the Marlinespike Chandlery. For more info on this piece, visit @thosmoser.

KS: Your work and craftsmanship of sea chests is intriguing! This is an object I had no idea existed, and yet its specificity in design alongside its history suggests a rich legacy. Please indulge me in the piece’s details.

TW: The sea chest was one of the first projects that I undertook that helped spur my interest in marlinespike work as a serious hobby. Something about the characteristic shape is what I found particularly appealing. The quintessential sea chest has sides that slope inward toward the top and is fitted with intricately woven marlinespike handles known as beckets. The reason for the canted sides is because sea chests were, as the name implies, used at sea, and on pitching and rolling deck floors. So if you are standing near it and leaning into the side of the chest, it's much easier on your shins and legs to lean against a sloped surface as opposed to a straight-sided box that would constantly be bruising your lower legs. They were mostly used by whalers who spent two to three years at a time on voyages so the sea chest was basically the sailor’s locker.

KS: Who are some of the inspiring creatives you look to and engage with in your day-to-day life?

TW: A couple of years ago, I discovered the work of Carl Auböck (II and III primarily) They worked in Austria in the 1930s through the 50s and 60s but the workshop is still in operation under the guidance of Carl Auböck IV. The work is mostly considered mid-century modern, but I felt a deep resonance with their aesthetic, techniques and material. Thinking about it now, I actually think the lines of a traditional sea chest could be considered MCM in form. I've been researching and collecting Auböck pieces since my discovery of their work, and I see my work emulated in their designs. It’s one of those instances where I thought I was doing something somewhat unique or new, but after discovering the Auböck line there are strong parallels.

“I think there is value in perturbations to old ideas and extracting the best elements of previous work and masterfully recreating those aspects.... I think many of the most successful designs for any product, piece of art or structure have parallels in the natural world, so really nothing is new in that sense.”

Cairns

KS: I have to ask, do you have any favourite nautical stories that you've enjoyed throughout the years? I know you’ve read Moby Dick at least a handful of times, but any others in addition to Melville's classic tale?

TW: Well, I don't really think of Moby Dick as a ‘nautical tale,’ if you know what I mean, but I did enjoy reading through the canon of Mutiny on the Bounty, In the Heart of the Sea, and Endurance. There is also a book titled the Cruise of the Cachalot that describes a much grittier version of life at sea as a whaler. The 1956 John Huston/Ray Bradbury/Gregory Peck movie version of Moby Dick was certainly an inspiration too, I've seen the movie countless times and can remember being fascinated by the tale and imagery on the screen as a child - which reminds me - the other favourite nautical tale from childhood was Burt Dow Deep-Water Man by Robert McCloskey. Incredible fate as well that I now live on the Island where the real Burt Dow lived and where McCloskey vacationed.

Collected items against blue wall, raw materials, lobster claws, rope making machine made by Whitten

KS: Do you have a creative philosophy that you abide by and hold to be true?

TW: I think it’s difficult to achieve a new design idea, and even if you think it’s new, there's a strong likelihood that it isn't. I don't know if that is any more true in the field of craft or fibre art, but I sense that some of the most appealing design components centre around elemental and organic geometry, so in a way that further constrains the set of the new design. But that's ok. I think there is value in perturbations to old ideas and extracting the best elements of previous work and masterfully recreating those aspects. I've used the word organic, and I think organic is a component of ergonomics, and I think many of the most successful designs for any product, piece of art or structure have parallels in the natural world, so really nothing is new in that sense.

To learn more about Tim and his work, visit his Instagram page and his website.

This feature was written by Kyra Shapurji.

By day, Kyra is a Program Manager but moonlights as a writer on culture, travel, and the creative arts. She feels most comfortable and at ease when she's in the company of artists and creatives chatting about books and inspiration for a project, and listening to others tell their life story.

In the past, Kyra was the Managing Editor at LoftLife, Assistant to Travel & Research Editor at Saveur and has written for Hôtel Weekend and HILUXURY Travel.

As a recent contributing writer for FAIRE Journal, she also currently writes for Fathom. She also believes strongly in volunteering in one's community, and for the last five years, Kyra was a mentor with NYC's Bigs & Littles program.

Kyra currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY, and when she's not out at a new restaurant, art exhibit or theatre show, she's got her nose in a book or The New Yorker and is most certainly planning her next travel itinerary. Her published work and blog can be found here, and for her latest travels find her on Instagram @shap_attack.